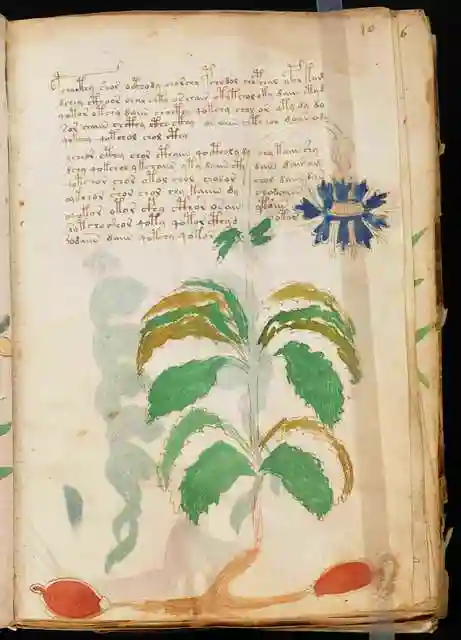

The Voynich manuscript is an illustrated handwritten in an unknown writing style known as ‘Voynichese.’ This have been carbon dated to the early 15th century, and stylistic research indicates that it was written in Italy during the Italian Renaissance.

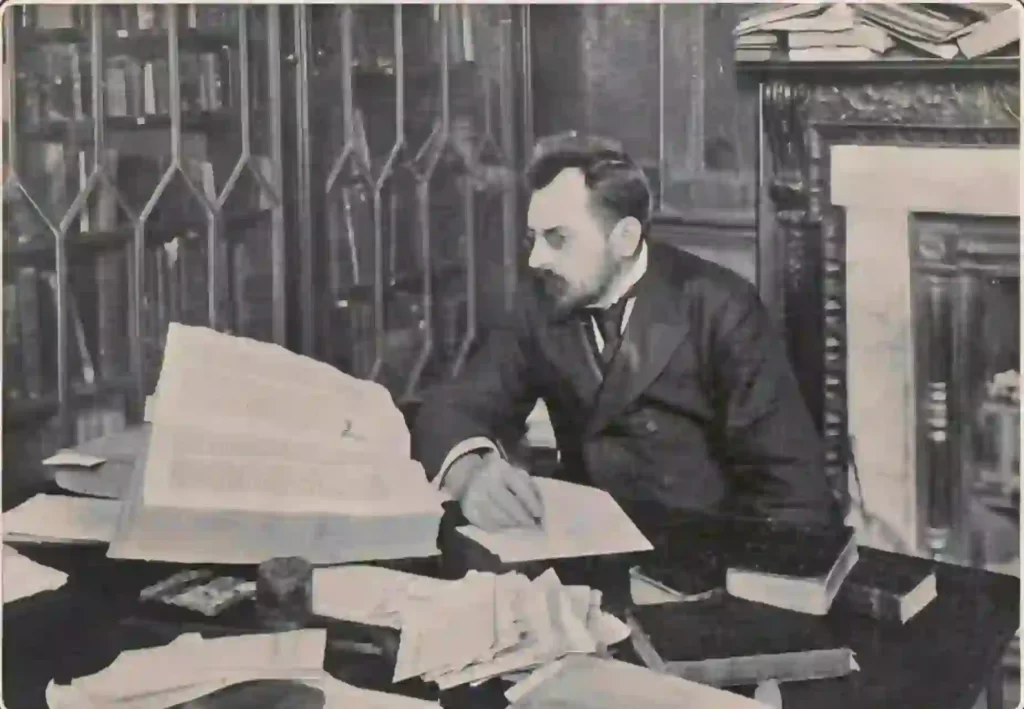

The origin, language, and date of the Voynich Manuscript—named after the Polish American historical bookseller Wilfrid M. Voynich, who obtained it in 1912 are as hotly discussed as its perplexing drawings and untranslated text.

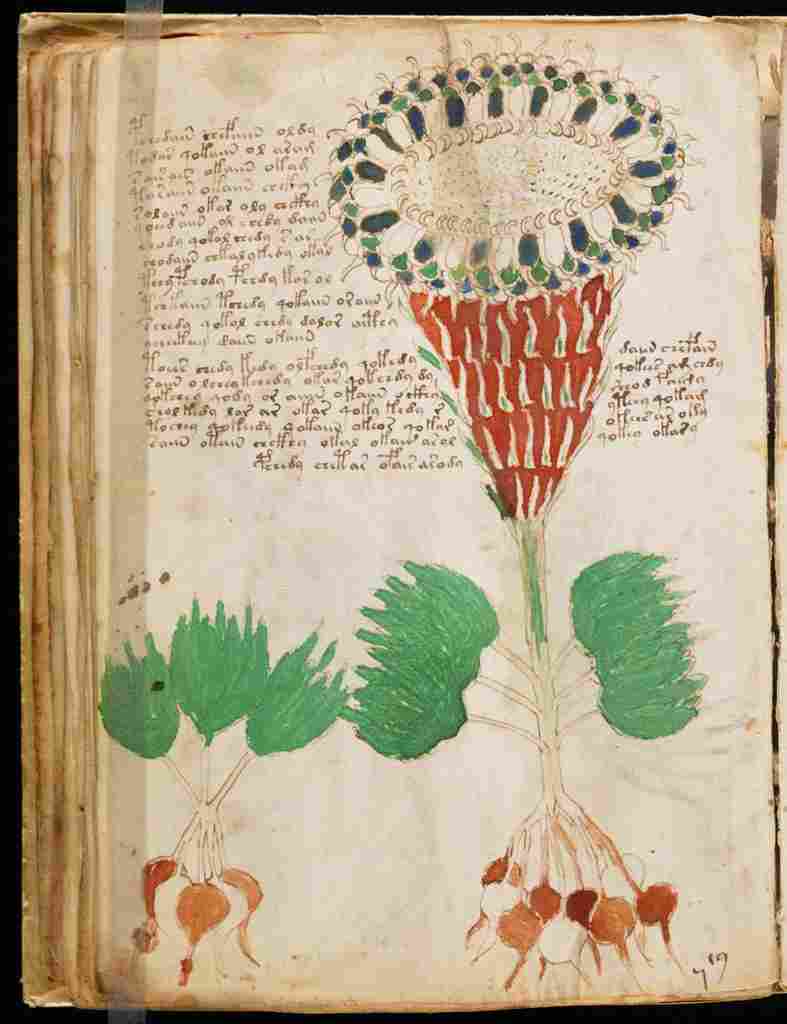

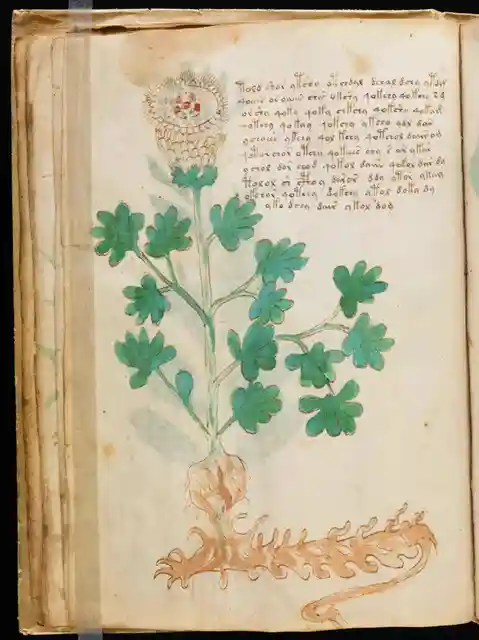

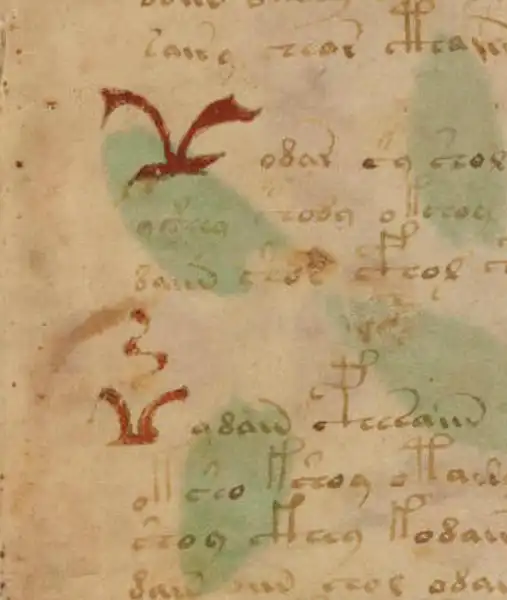

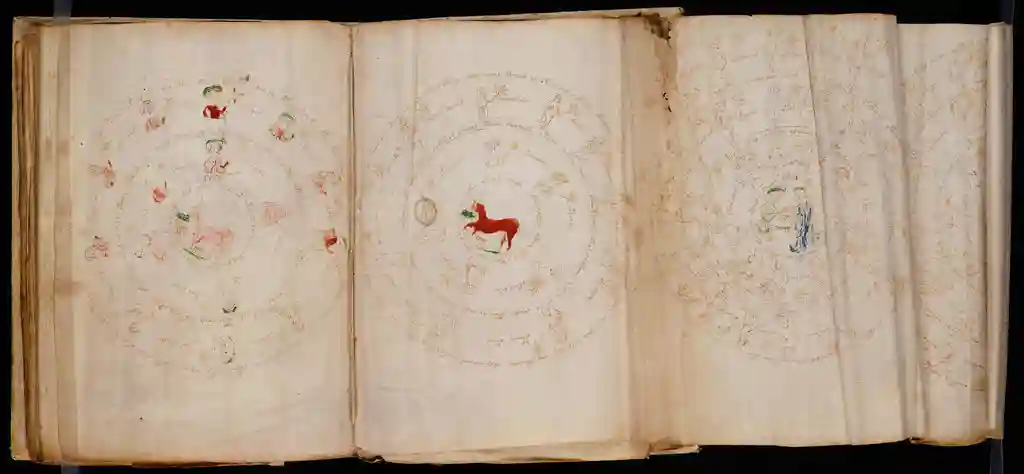

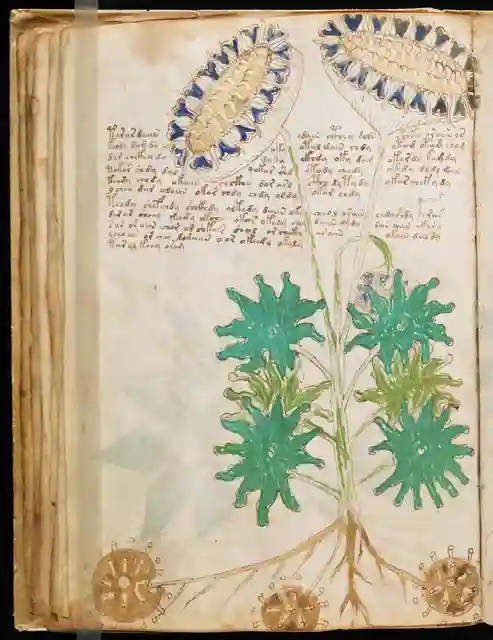

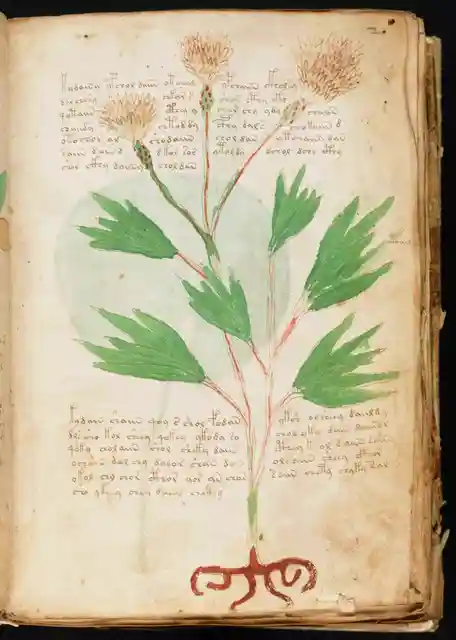

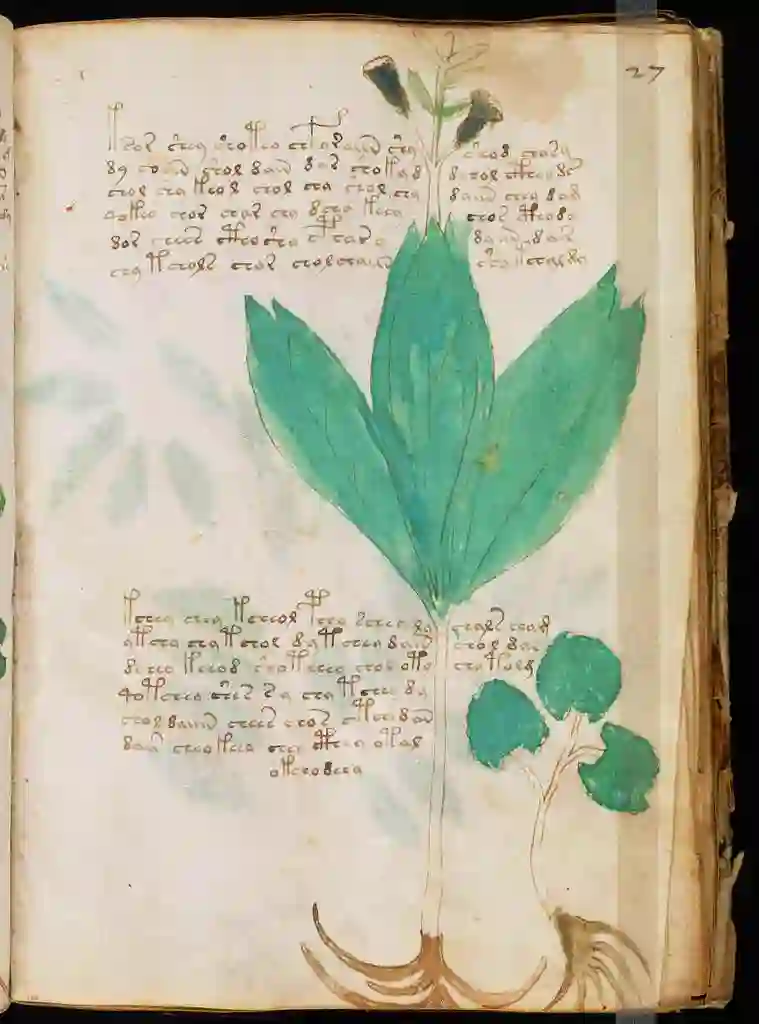

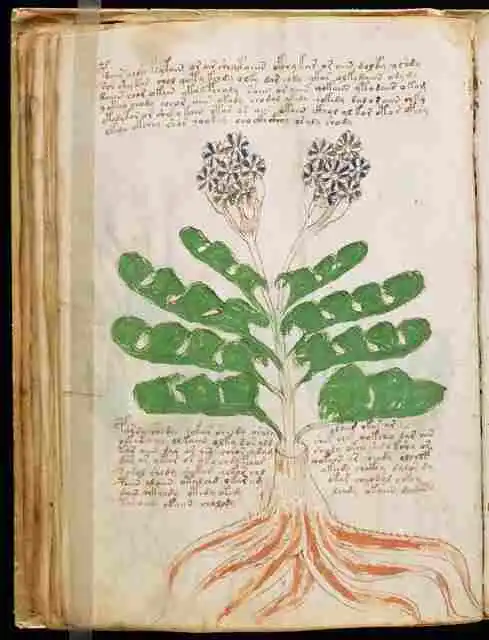

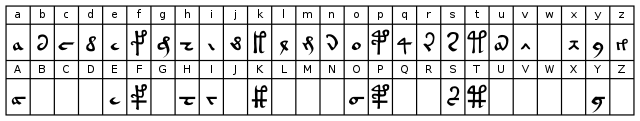

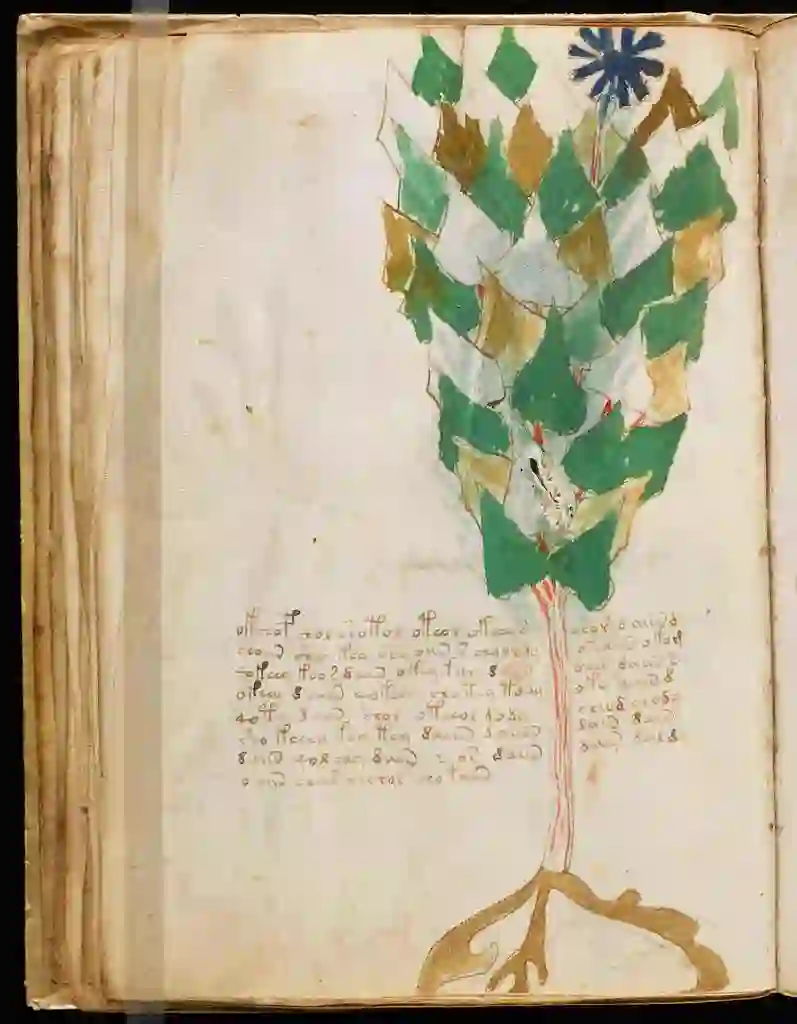

Nearly every page of this magical or scientific text features botanical, figurative, and scientific drawings of a provincial but dynamic character created in ink with colorful washes in multiple colors of blue, yellow, brown, red, and green.

Some consider the manuscript to be a fake, a mixture of meaningless words and images. Others perceive it as a mystery with important mysteries.

What are the Contents of the Voynich Manuscript?

The Voynich Manuscript is divided into six sections: The Voynich codex is 22.5 16 cm (8.9 6.3 inches) in length and has 102 lavishly illustrated parchment pages (about 234 pages).

Many pages have large drawings or charts that have been colored with paint. A recent examination employing polarized light microscopy revealed that the text and figure outlines were created with iron gall ink and quill pen. The inks used in the drawings, text, page, and quire numbers all share identical microscopic properties.

The section on plants is the longest, accounting for slightly more than half of the manuscript. Several zodiac charts and depictions of the sun and moon are included in the astrological section. The portion with the bathing nymphs is often referred to as the balneological section, which refers to the science of baths and bathing.

A pharmaceutical part illustrates what appear to be natural cures — plant roots next to medicinal bottles — and a fifth, unillustrated area contains blocks of text delineated by tiny stars.

An exquisite, looping script of 25 to 30 characters glides down the pages in brief paragraphs, interwoven with detailed pictures, from left to right.

1. Botanical featuring 113 unidentified plant species drawings

2. Astronomical and astrological drawings, such as celestial charts with radiating circles, suns and moons, a bull and an archer, Zodiac symbols such as fish, exposed females coming from pipes or chimneys, and elegant figures.

3. biological parts with a plethora of drawings of small female figures, most with swollen abdomens, immersed or wading in fluids, and strangely interacting with interconnected tubes and capsules.

4. A complex collection of nine cosmology medallions, several of which are drawn across several folded folios and show possible geographical formations.

5. Pharmaceutical drawings of over 100 distinct kinds of medicinal herbs and roots depicted with red, blue, or green jars or vessels, and

6. continuous pages of text, possibly recipes, with star-shaped flowers in the margins marking each item.

Who Wrote the Voynich Manuscript and the Ownership History

The manuscript’s exact location and date are unknown, although significant research suggests it was created somewhere in central Europe, and radiocarbon analysis dates it to the early 15th century.

One long-held theory, refuted by radiocarbon dating in 2009, was that the 13th-century English scientist Roger Bacon penned it. The manuscript’s first owner could have been Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II, who reigned from 1576 until 1611. If Rudolf did own it, one notion is that he bought it from mathematician John Dee for 600 ducats, though this claim has not been adequately verified.

The manuscript traveled from Rudolf to the court pharmacist Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz, who signed it on the inside, and then to Johannes Marcus Marci, a royal doctor, and scientist.

Marci brought the manuscript from Prague to the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher in Rome in 1665 or 1666, believing that Kircher might decipher its encryption. It was then in possession of the Jesuits until Voynich purchased it. When Voynich bought the manuscript in 1912, the note was slipped within the pages.

Voynich refused to reveal the manuscript’s prior owner, prompting many to believe he wrote it himself. However, after Voynich died, his widow claimed he bought the book at the Jesuit College in Frascati, near Rome.

The manuscript was possessed by Rudolf’s court chemist and pharmacist Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenec, who left his signature (detectable with ultraviolet light) on folio 1r.

The next owner of the Voynich manuscript was a friend of the letter writer Marci, Baresch, who transferred the manuscript to Marci. Before his death in 1667, Marci forwarded it to the scholar and Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher.

Decoding Attempts of the Voynich Manuscript

• Initially, it drew mainly humanities scholars. In 1921, William Newbold, a philosopher at the University of Pennsylvania with interest in cryptography, claimed that it was written as a scientific book by a 13th-century Franciscan. Each mysterious letter, according to Newbold, was essentially a combination of microscopic symbols discernible under sufficient magnification.

• William and Elizebeth Friedman, pioneers of modern cipher-breaking, proceeded to work on the manuscript using codebreaker techniques. Despite studying other texts and being recruited to decrypt signals during both world wars, they could never solve the Voynich.

• Some researchers are drawn to cryptic drawings. Since 2013, botanist Arthur Tucker has asserted that the Voynich plants were indigenous to the Americas in the 16th century.

In a recent email, he stated that his non-computational approach to understanding each botanical picture sparked outrage from more data-focused academics, whose techniques he derided as “circular reasoning” without elaboration. However, neither botanists nor data scientists have accepted his theory.

• In 2013, a team of scientists in Brazil and Germany conducted their own statistical analysis and came to the opposite conclusion: the text was most likely written in a language and was not generated randomly.

• In 2016, Greg Kondrak, a computer scientist at the University of Alberta, and his student, Bradley Hauer, used a machine learning algorithm trained on translations of the same block of text to hypothesize that the material is jumbled-up Hebrew written in an unusual script.

Many amature and professional cryptographers, including American and British codebreakers from both World Wars, have studied the Voynich manuscript.

The manuscript has never been decoded, and none of the several ideas presented over the last century has been objectively verified. The mystery of the manuscript, its meaning, and its origin have piqued the public’s interest, prompting research and discussion.

The manuscript has only a few words written in what appears to be a Latin script. Except for two sentences in the regular script, the last page contains four writing lines in highly distorted Latin letters. The lettering is similar to European alphabets from the late 14th and early 15th centuries, but the words do not appear to be in any language.

In addition, the names of ten months (from March to December) are printed in Latin script in a sequence of pictures in the “astronomical” section, with spelling reminiscent of medieval languages spoken in France, northwest Italy, or the Balkans. However, whether these fragments of Latin script were originally part of the text or were added afterward is unknown.

Is Voynich Manuscript a Hoax or Real

The Voynich manuscript being a hoax cannot be ruled out. But if the Voynich is a forgery, it’s a good one. In anticipation of the development of radiocarbon dating, a twentieth-century con artist would have had to locate a hundred and twenty sheets of blank six-hundred-year-old vellum.

Scholars are still highly split on whether the text is likely to be important. However, the distribution of letters and words is far from random, exhibiting statistical traits commonly associated with natural-language readers—properties that were not found until the 1930s.

And while no single word has been decoded, recent research has revealed distinct vocabularies coinciding with the manuscript’s division into sections, such as “herbal” and “astronomical.

Certain words found with plant illustrations do not appear near astronomical diagrams, and vice versa, precisely what you’d expect from a meaningful text organized by topic.

Different Theories on Voynich Manuscript

Some think that the Voynich Manuscript was written with the assistance of aliens and that the book describes alien medicine and vegetation.

Some believe the book contains Roger Bacon’s early findings and inventions. However, it could also be a pidgin prayer book from a heretical Christian sect or a worthless compilation of nonsense sold for monetary benefit by an occult philosopher.

Conclusion

A surprising amount of qualitative and quantitative methodologies have been used to date in trying to obtain insight into the manuscript. In terms of quantitative approaches, well-established language empirical laws were investigated initially.

Nothing about the Voynich manuscript excites more than the fact that it was written in a mystery language with a unique alphabet. It could be an existing language represented in code or one created specifically for this book.

The Voynich manuscript may be a compilation of information on herbal remedies, therapeutic bathing, and astrological readings concerning the female mind, body, reproduction, parenting, and the heart in full compliance with the Catholic and Roman pagan religious beliefs of Mediterranean Europeans during the late Medieval period.

Unsurprisingly, with so much unknown, determining the purpose of the Voynich Manuscript is impossible. For the time being, the best guess is that it is a work of medical, magical, or scientific thought. Still, our understanding may evolve as scholarly research discovers new evidence.

The manuscript is now housed at Yale University’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.