Last updated on July 19th, 2023 at 06:40 am

In February 1933, the entire country was shocked to learn of an unimaginably terrible double murder in the town of Le Mans. Two respected, middle-class ladies, mother, and daughter had been killed by their housemaids, two sisters.

For years, these ladies plagued the French city of Le Mans with the knowledge of their heinous acts. Christine and Léa Papin will go down in French history as two of the twentieth century’s most terrible villains.

It also sparked the curiosity of many French intellectuals, who authored various interpretations of the case or dramatized the tragic incident for theater and film.

The Papin Sisters’ Family

There are three Papin sisters in all, and they all had terrible lives. Emilia was the oldest sister, followed by Christine, and Léa was the youngest. The three sisters were exposed to horrific maltreatment throughout their childhoods, and despite their age disparities, Christine and Léa were quite close.

Christine and Léa Papin grew up in the western French hamlet of Le Mans. Their age gap was seven years, yet it didn’t appear to affect their friendship. Emilia, their eldest sister, became a nun at a monastery.

Christine and Léa were raised in a troubled environment, where they witnessed violence and many sorts of abuse. Both daughters were transferred to a mental hospital shortly after their parents split to heal from the divorce, which had had a significant impact on them.

Following the divorce, their mother also abandoned them. As a result, it had always been Christine and Léa Papin vs. the world.

The Crime

René, a retired lawyer, shared his home with his wife, Léonie, and their 27-year-old daughter Geneviève. He recruited Christine and Léa because they work 14 hours daily and take just one half-day off weekly. René had no idea he was bringing his family’s killers into his home.

They collaborated whenever they could, which is how they found themselves in the Lancelin home in 1926. Christine initially began working there, and after a few months, she convinced the Lancelins to hire Léa.

Christine and Léa stayed close and were usually together. They were silent, spoke little, and kept in their bedroom even when granted breaks. On Sundays, they went to church together but did very little in terms of leisure activities. When they did leave the Lancelin house, it was usually to perform family errands.

When Madame Lancelin discovered that they were transferring their salaries to Clémence, she stopped them from doing so to protect their interests. Clémence was even informed that the girls would no longer be paying her. Nevertheless, the Lancelins employed the girls for seven years without incident.

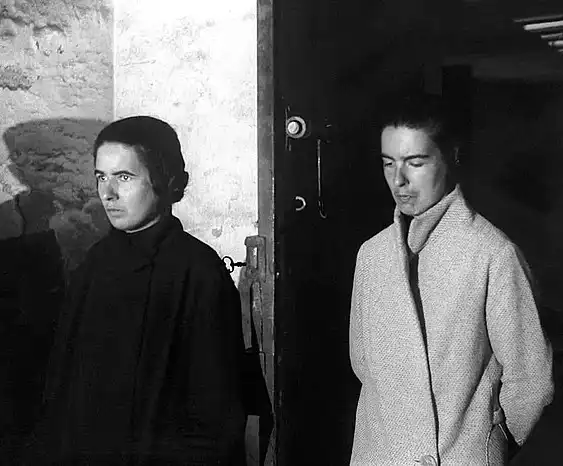

Four women were engaged in a horrific murder: the victims, a mother and daughter, and their maids, sisters Christine and Léa Papin, who perpetrated the crime. The tragedy sparked several ideas about what motivated the two young ladies to kill.

René Lancelin, a former solicitor, his wife Léonie, their 27-year-old daughter Geneviève, and their live-in servants, Christine Papin, 27, and Léa Papin, 21, made up the household.

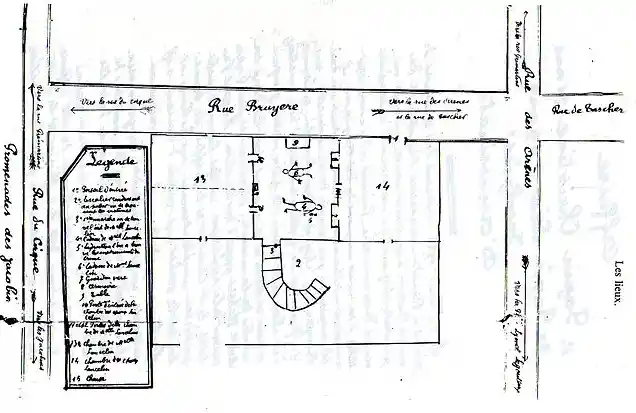

René had been playing cards with friends at another residence on the day in question but had planned to call home to pick up his wife and daughter so they could all go out to dinner together. Instead, he discovered a closed front door and a dark home.

He hadn’t brought a house key with him, so he had to rely on a police officer to get admission on his behalf.

When the cops came, they discovered that the only way inside the house was to scale the rear wall and enter through the back door. Unfortunately, the officers had to make their way into the residence in the dark since the fuses had blown.

When they arrived at the stairs, they discovered the deaths of Madame Lancelin and Genevieve. After resetting the fuses and turning on the lights, the authorities could determine what had occurred to the two women.

Madame and Genevieve’s features were virtually unrecognizable due to the severe damage inflicted on them. Their faces were bashed in, and each woman’s eyes had been ruthlessly removed.

The women’s thighs and legs had been maimed, but most of the assault had been directed at the victims’ faces. The police assumed instantly that a mad guy had attacked the women because who else could have administered the savage blows that demolished the women’s faces so severely?

When the police noticed the blood trail up the stairs, they proceeded to track the droplets, one by one, to the attic.

The maids were locked up in their chamber at the top of the house. When this was dismantled, they were discovered naked in bed together. They quickly admitted to the killings.

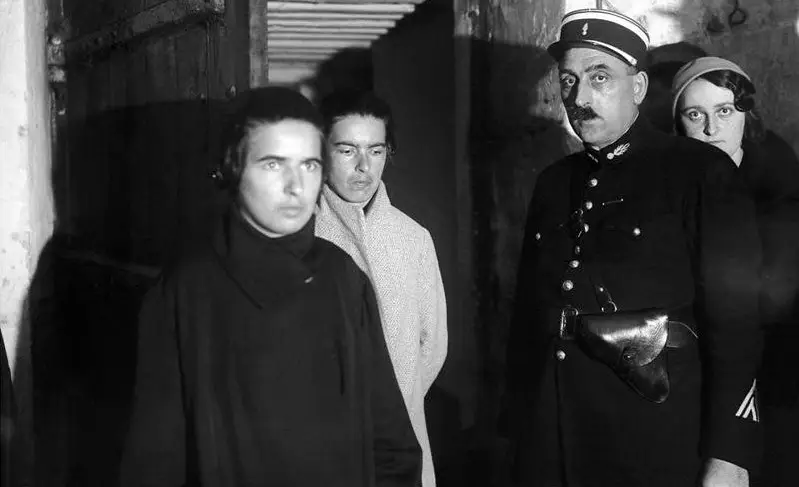

The Police Investigation and the Trial

Christine got quite upset since she couldn’t see Léa. Prison officials eventually relented and allowed the two sisters to meet. Christine is said to have thrown herself at Léa, unbuttoning her shirt and pleading with her, “Please, say yes!” implying an incestuous physical relationship.

Christine had a “fit,” or incident, in July 1933, in which she attempted to remove her own eyes and had to be restrained. She subsequently provided a statement to the magistrate stating that on the day of the killings, she had an episode similar to the one she was experiencing in jail, which prompted the murders.

Christine and Léa had symptoms of mental illness, such as avoiding eye contact and looking straight ahead as if in a fog. As a result, the court authorized three physicians to conduct psychiatric assessments on the sisters to ascertain their mental state.

They determined that the two had no mental illnesses and were sane and able to face trial. They also concluded that Christine’s passion for her sister stemmed from familial bonds, not an incestuous relationship, as some had indicated.

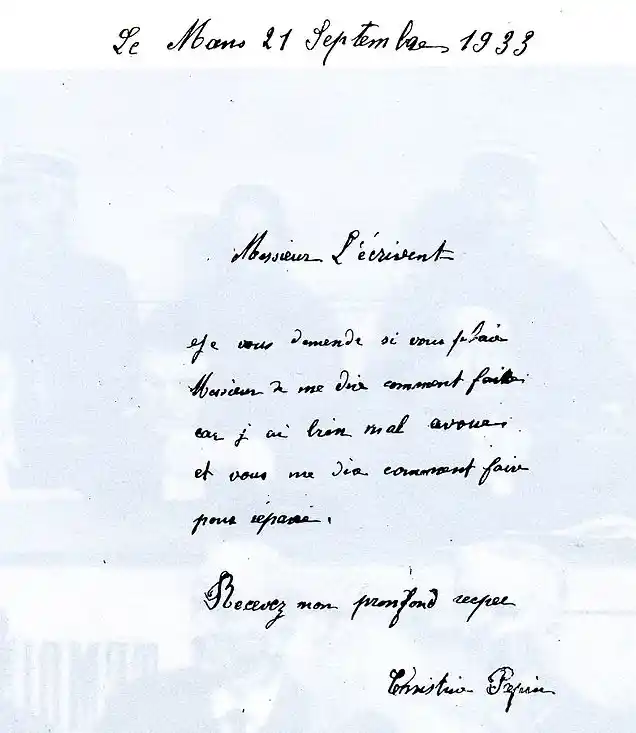

During the September 1933 trial, however, medical testimony revealed a family history of mental illness. Their uncle had committed himself, and their cousin was in a mental institution. Nevertheless, the psychiatric community fought and disputed the sisters’ diagnosis.

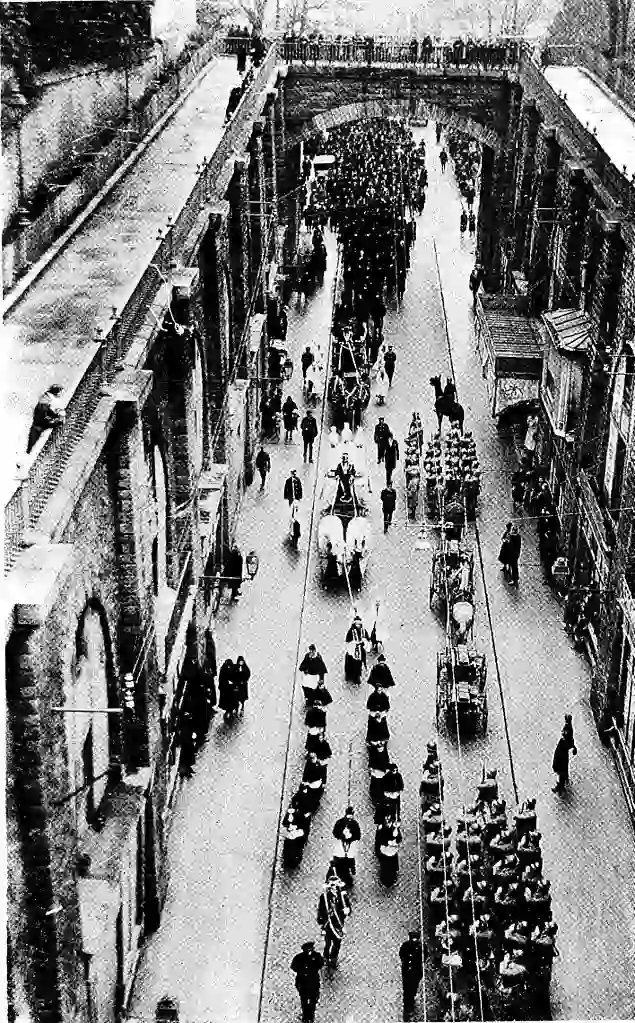

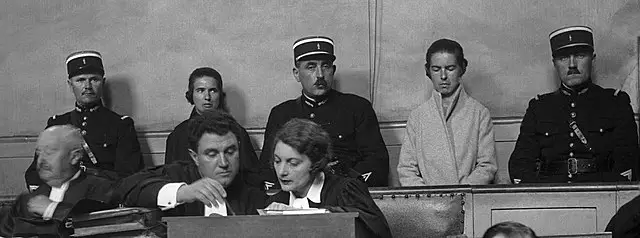

The trial, held in September 1933, was a national event that was attended by a significant number of members of the public and the press. The mob outside the crowded courthouse had to be controlled by police, who were brought in. During the trial, the judge had to threaten to empty the court to calm the emotional reactions of those in the public gallery, especially when eye-gouging was depicted.

After considerable thought, it was determined that Christine and Léa had “Shared Paranoid Disorder,” which is thought to arise when groups or pairs of individuals are separated from the outside world, developing paranoia, and one partner dominates the other. This was especially true of Léa, whose quiet demeanor was eclipsed by the stubborn and domineering Christine.

After the trial, jurors deliberated for 40 minutes before deciding that the Papin sisters were guilty of the crime charged against them. Léa, who was deemed to be under the influence of her older sister, was sentenced to ten years in prison. At first, Christine was sentenced to death by guillotine, but her sentence was eventually changed to life in prison.

Later Life of Papin Sisters

Christine’s health progressively deteriorated in jail. She refused to eat since she was so unhappy at being separated from Léa that she became gradually sick. Finally, she was sent to a mental institution in Rennes, where she never improved and died in 1937.

Léa was freed from jail in 1941 after having her sentence shortened for good behavior. Her mother, Clemence, then joined her, and they moved to Nantes, south of Rennes.

Léa worked as a hotel chambermaid under the guise of Marie. L’Affaire Papin, written by French novelist Paulette Houdyer in 1966, recounts the story of the Papin sisters.

A journalist from France-Soir apparently interviewed Léa as a result of this book. According to this interview, she had intense visions of Christine standing before her in spirit form and was convinced that her sister was in heaven.

She still possessed photographs of Christine and an old trunk full of exquisite outfits that the girls had fashioned for themselves before their deaths. She also maintained that she was saving to go back to Le Mans and rejoin her other sister, Emilia, but no evidence suggests that she did so.

The interview in France-Soir is the last documentation of the Papin sisters’ life.

For many years, it was assumed that Léa died in 1982 at the age of seventy. However, a documentary filmmaker named Claud Ventura claimed in 2000 that he discovered Lea was still alive and residing in a hospice while working on a documentary on the sisters.

Although this woman passed away in 2001, the jury is still unsure whether he was accurate.

Scientific Theories Behind Their Behavior

The sisters’ commitment to one another was the one constant in their life and their sole permanent emotional relationship. They collaborated whenever they could, which is how they found themselves in the Lancelin home in 1926.

Christine initially began working there, and after a few months, she convinced the Lancelins to hire Lea. Christine was a cook, and Lea was a chambermaid.

Their interaction with the family appears to have been minimal, and their bosses appeared to be uninterested in speaking with them. They shared a room on the top level of the Lancelins’ three-story terrace and spent most of their time alone. They attended Mass every Sunday but seemed to have no other interests outside each other.

Psychologically, the girls were entangled in what the French call folie a deux: literally, lunacy in two, also known as shared paranoid illness.

This disorder is most common in small groups or pairs who grow secluded from the outer world and live an intense, inward-looking existence with a paranoid perception of the outside world. The majority of murderous couples have this type of insular, inward-looking relationship.

It is also characteristic of shared paranoid illness for one couple to control the other, as the Papin sisters demonstrated.

According to several witnesses, Christine became increasingly angry and manic in the months preceding the killings. In addition, her health was deteriorating, and on the evening of February 2, 1933, her insanity reached a climax.

Conclusion

Although little recognized outside of France, the Papin sisters have had an influence that few persons, criminal or otherwise, have had throughout the years. So far, they have produced three plays, three films, and a handful of books based on these infamous females, in addition to innumerable articles.

Most celebrities, French or otherwise, cannot boast of such a track record. Nevertheless, the Papin sisters have an incredible ability to captivate people, fascinate them, and inspire them to be intellectual and artistic endeavors. Only Jack the Ripper is likely to have elicited a more remarkable outpouring of emotion.

Some speculated that the sisters had folie à deux, a mental disease that caused them to hear voices, feel intense paranoia, and violently snap on the Lancelins—given their family background.

Many observers, however, saw the sisters’ acts as nothing more than a revolt against the upper class. They interpreted their violent actions as retaliation for the Lancelins’ cold, harsh, and disconnected treatment of the two.

Christine and Léa Papin perpetrated a heinous act on February 2, 1933. But were they driven by insanity, bloodlust, or class warfare? We still don’t know—it’s one of many unsolved issues about this fascinating case that has lasted over a century.