Belle Gunness | The Story of Hell’s Bell Murders

Last updated on December 1st, 2022 at 10:16 am

Belle Gunness, also known as Brynhild Paulsdatter Størset, was a Norwegian-American serial killer who operated in Illinois and Indiana from 1884 until 1908.

She is responsible for so many deaths that detectives have ceased counting the number of bodies discovered on her premises.

Belle Gunness is suspected of having murdered at least fourteen people, most of them were men she invited to visit her rural Indiana farm with the promise of marriage. However, some sources speculate that she was involved in as many as forty murders.

The Life of Belle Gunness

Brynhild Paulsdatter Størset ( Belle Gunness) was born on November 11, 1859, in Selbu municipality, Norway, to Paul and Berit Størset; she was the youngest of eight children. In 1874, she was confirmed at the Evangelical Lutheran Church.

At 14, she began milking and herding cattle for adjacent farms to save money for her trip to New York.

In 1881, she immigrated to the United States.

She changed her initial name to Belle while being processed by immigration at Castle Garden, then traveled to Chicago to join her sister, Nellie, who had arrived several years before.

According to one widely circulated but unproven story, she was pregnant when she was about 17-18 years old and went to a rural dance. She was attacked while there by a man who allegedly kicked her in the abdomen, causing her to miscarry. Norwegian authorities never charged the man because he came from a wealthy family.

However, locals claimed that Brynhild’s personality altered dramatically after it. After a short time, the person who had kicked her died of stomach cancer, according to reports.

Belle Gunness married fellow Norwegian immigrant Mads Sorenson in 1884. The loving couple ran a confectionery shop and cared for foster kids. However, Belle Gunness’ candy business was not a success, and after a year, a fire broke out and burned the store down.

Fortunately, the firm was insured, and Belle Gunness informed authorities that an exploding kerosene lamp had started the fire. Although no such lamp was discovered, the investigators paid Belle the insurance money. Soon after receiving the compensation, the couple purchased their first home, which was likewise destroyed by fire in 1898.

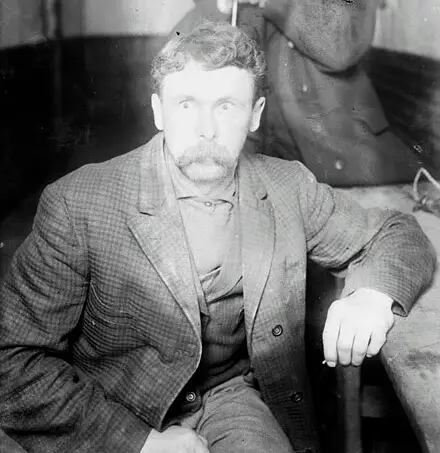

The Appearance of Belle Gunness

She was described as “masculine in look” and stood around 5’7″ (170cm) tall and weighed about 210-250 pounds.

Crimes Committed by Belle Gunness

The couple’s four children were Caroline, Axel, Myrtle, and Lucy. Caroline and Axel died as newborns due to acute colitis, including nausea, fever, diarrhea, lower abdominal discomfort, and cramping, which are also symptoms of many other types of poisoning. They collected on both children’s life insurance policies.

On June 13, 1900, Gunness and her family were listed on the United States Census in Chicago as the mother of four children, only two of whom were still alive: Myrtle A. and Lucy B. In addition, an adoptive 10-year-old girl named Morgan Couch, later known as Jennie Olsen, was also counted.

Albert Sorenson died on July 30, 1900, the day his two life insurance policies overlapped. The first doctor who examined him suspected strychnine poisoning. But, the Sorensons’ family doctor, who treated him for an enlarged heart, decided that heart failure was the reason behind his death. Because the death was not deemed suspicious, an autopsy was considered unnecessary.

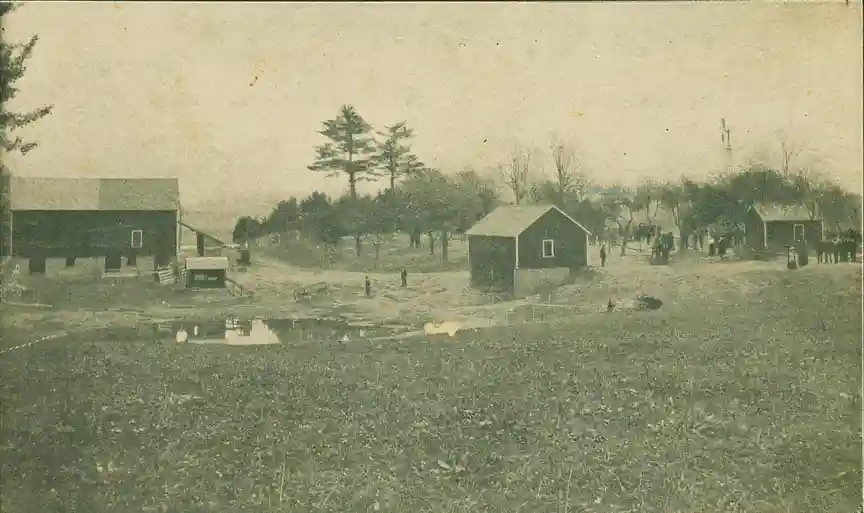

Even though her husband’s family wanted an investigation, saying Belle poisoned her spouse to collect on the insurance, no charges were filed. She was eventually granted $8,500 (about $270,000 today), which she used to purchase a farm on the outskirts of La Porte, Indiana. The boat and carriage homes were alleged to have burned down shortly after she purchased the property.

And before long, the widowed Gunness was no longer a widow. She married Peter Gunness in April 1902.

Strangely, tragedy appeared to be returning to Belle Gunness’ doorstep again. First, Peter’s prior relationship’s infant daughter perished. Then Peter died as well. He had apparently been hit on the head by a sausage grinder that had fallen off a shaky shelf. The coroner called the occurrence “a little strange” but concluded it was an accident.

Gunness took possession of her husband’s life insurance coverage.

Only one individual seems to notice Gunness’ habits: her foster daughter Jennie Olsen. Olsen allegedly told her classmates, “My mama killed my papa.” “She killed him with a meat cleaver.” Don’t tell anyone.”

Olsen vanished shortly after. Her foster mother stated she was sent to school in California at first. Years later, though, the girl’s body was discovered in Gunness’ hog pen.

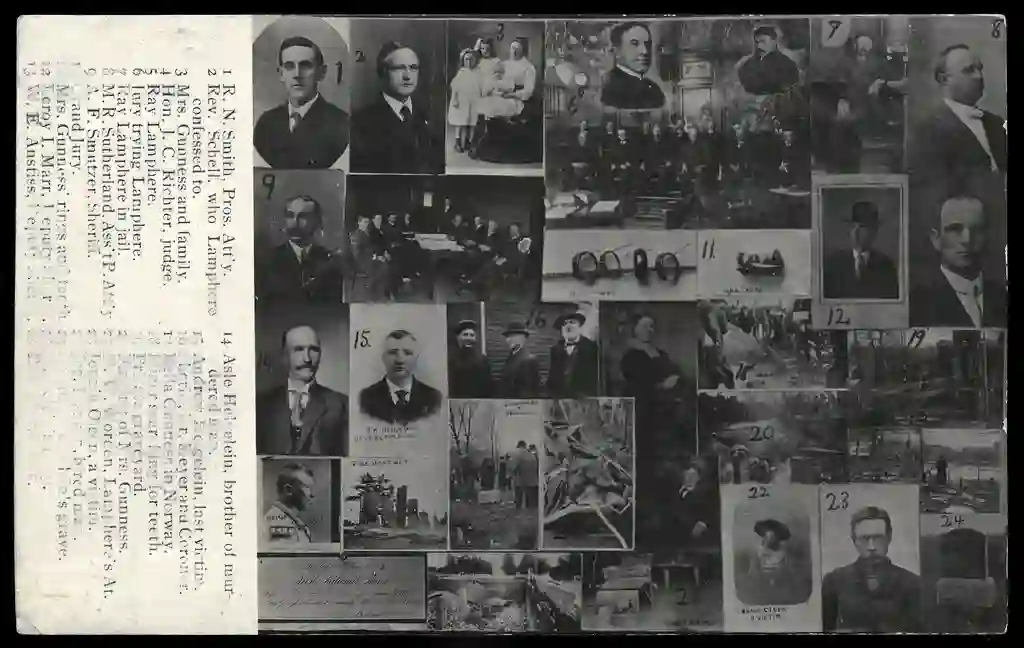

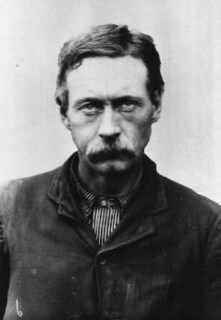

Ray Lamphere, a farmhand, was hired to help with chores in 1907. However, news quickly spread that Belle’s relationship with Lamphere was more than just business.

Lamphere frequently boasted about sleeping with his employer while drinking, which surprised others who only viewed Belle as the big lady who loved to dress in men’s overalls and handle her own hog slaughtering. But Lamphere saw another side to the woman, and the rest of the town would soon as well.

Lamphere would not be enough for Belle. She desired more and soon began looking for new suitors by placing the following advertisement in the lovelorn section of newspapers in major midwestern cities:

She advertised her marriage in the Midwestern Norwegian-language newspapers Skandinaven, Minneapolis Tidende, and Decorah-Posten.

Henry Gurholt, a Wisconsin farmhand, responded to one of her advertisements. Gurholt wrote his family after visiting La Porte that he liked the land, was in good health, and asked them to send him seed potatoes. When they didn’t hear from him after that first letter, the family contacted Gunness, who informed them that Gurholt had gone to Chicago with horse traffickers.

In 1906, John O. Moe of Minnesota also responded to an ad. But, after several months of correspondence, he went for La Porte, having withdrawn a considerable sum of money from his bank account, and he just vanished. Then, finally, a carpenter who did freelance work for Belle noticed Moe’s trunk and more than a dozen others in Belle’s house.

Next up was Ole Budsberg, an old widower from Iola, Wisconsin. He was last seen alive on April 6, 1907, at the La Porte Savings Bank, where he mortgaged his Wisconsin farm, signed a document, and received several thousand dollars in cash.

Budsberg’s sons were unaware that their father had gone to Gunness. When they finally found out where he was going, they wrote to her, and she swiftly replied, saying she had never seen their father.

Several additional middle-aged males visited and vanished during brief visits to the Gunness farm in 1907. Then, in December 1907, she got a letter from Andrew Helgelien, a bachelor farmer from Aberdeen, South Dakota. The couple exchanged several letters until a letter arrived that completely floored Helgelien, written in Gunness’ meticulous handwriting and dated January 13, 1908.

When Andrew did not return home, Asle wrote to Belle to inquire about his sibling’s whereabouts. Gunness responded by informing Asle Helgelien that his sibling was not at her farmhouse and had most likely traveled to Norway to visit relatives. Asle answered that he did not believe his brother would do such a thing and thought his brother was still living in the La Porte region.

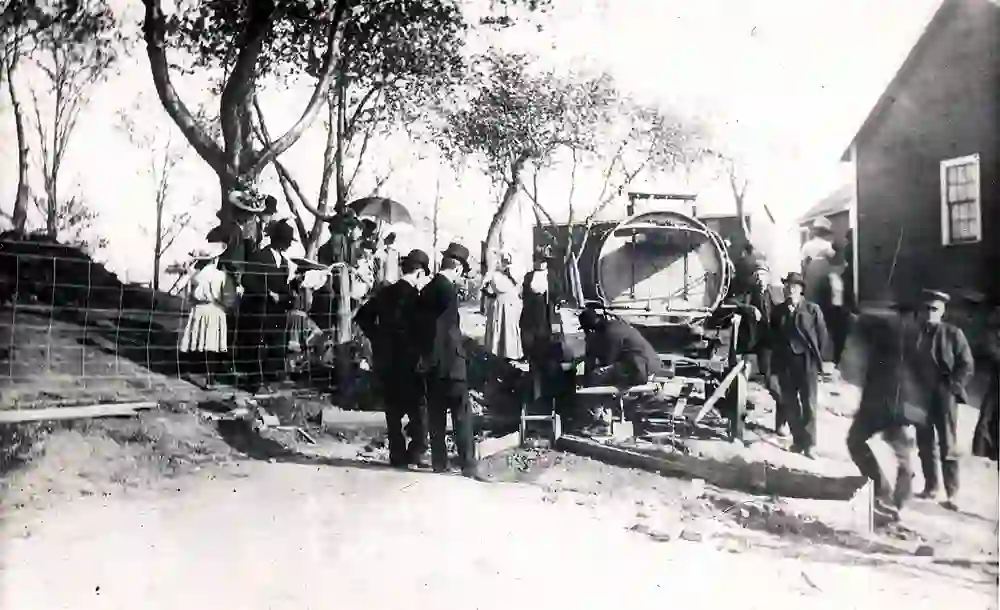

No one knew the full depth of Gunness’ crimes until a fire ripped through her La Porte home in April 1908, and Asle Helgelien informed authorities that he feared his brother, one of her suitors, had been involved in some foul play.

The murder farm was discovered as a result of the subsequent search. According to Johnson, 10,000 to 15,000 people turned out to see the police dig. In addition, gawkers purchased postcards featuring images of the deceased.

Investigators initially thought the bodies belonged to Belle Gunness and her three children: Myrtle, age eleven; Lucy, age nine; and Phillip, age five. But there were doubts from the start about whether the headless corpse belonged to Belle Gunness.

The woman in the fire was around 5′ 3′′ tall and weighed about 125 pounds, making her much smaller than Belle Gunness. Furthermore, the corpse was seen by multiple neighbors and friends, including two neighboring farms and several friends who said it was not Belle.

The Investigation Following the Fire

Following the discovery of bodies believed to be of Gunness and her children following the fire at the Gunness homestead, Asle Helgelien contacted La Porte police authorities, who had discovered mail between his brother, Andrew Helgelien, and Belle Gunness; the letters included requests made by Gunness for him to relocate to La Porte, bring money, and keep the move a secret.

During a visit to the Gunness farm, Asle Helgelien noticed “soft depressions” in what had been converted into a hog pen; while digging one of the depressions in the farm, a gunny sack was discovered containing “two feet, two hands, and one head,” which Helgelien recognized as those of his brother.

An immediate inspection of the site revealed dozens of such slumped depressions in the Gunness yard, and further digging and investigation yielded multiple burlap sacks containing “torsos and hands, arms hacked from the shoulders down, masses of human bone wrapped in loose flesh that dripped like jelly” from trash-covered depressions that proved to be graves.

In each case, the body had been butchered in the same way: the head had been severed, the arms had been severed at the shoulders, and the legs had been severed at the knees.

Lamphere claimed that Gunness urged him to set fire to the farmhouse while her children were inside. Lamphere further claimed that the body supposed to be Gunness’ was a murder victim who had been chosen and planted to deceive police.

One victim’s brother had alerted Gunness that he would be arriving at the farm soon to investigate his brother’s disappearance. According to Lamphere, Gunness was inspired by the approaching visit to demolish her house, fabricate her own death, and depart. Lamphere was wearing John Moe’s overcoat and Henry Gurholt’s watch when he was detained.

Disappearance of Gunness

On May 22, 1908, Ray Lamphere, Gunness’ hired man, was arrested for murder and arson. He was convicted of arson but not of murder. Lamphere died in prison, but not before confessing the truth about Belle Gunness and her misdeeds, including burning down her own house — the body found was not hers.

Gunness had planned everything and left town after removing most of her money from her bank accounts. She was never found, and her death was never confirmed.

Many people who knew Belle, including her neighbors C. Christofferson and L. Nicholson, as well as old friends such as Mrs. Austin Cutler and Mr. Sigward Olsen, examined the decapitated body and denied it was Belle’s. Other inquiries by authorities suggested the same thing.

In 2008, DNA testing was undertaken on the headless corpse trying to compare the DNA in the corpse to a sample from a letter Gunness had given to one of her victims. Still, the sample could not be adequately examined due to its age.

Ray Lamphere’s Confession

Ray Lamphere, the farm hand, quit her employ on February 3, 1908, due to a disagreement with Mrs. Gunness and found work on a farm owned by John Wheatbrook, not far from the Gunness estate.

After Lamphere left Mrs. Gunness, he constantly hinted that if he wanted to chat, he could make it fascinating for her, but her only answer was that Lamphere was “mad.”

Sheriff Smulzer arrested him since it was shown convincingly that he was on the ground when the fire erupted.

Rev. E. A. Schell recounted a confession made by Lamphere on his deathbed on January 14, 1910.

Lamphere told Schell about his employer’s treatment of her suitors, including murdering them, dissecting their bodies, and burying their remains in the hog pen. However, he claimed that she would occasionally feed the dissected bodies of the corpses to the hogs rather than bury them.

Lamphere claimed Belle was behind the arson plot. A few days before the incident, she hired a woman from Chicago. She murdered the woman, beheaded her body, dressed it in her clothes, placed her own fake teeth near the headless corpse to identify it as her own, and threw the woman’s head into the water. She then murdered her children and set fire to the house.

Lamphere admitted to assisting her in the plot, but Belle eventually betrayed him as well, just disappearing in the woods without ever meeting him. Instead, according to other stories, he accompanied her to Stillwell, where she boarded a train to Chicago.

Lamphere made another confession, this time admitting to killing Belle. However, the contradictions in the two confessions and the life of Belle Gunness remain a mystery.

Conclusion

A permanent Gunness exhibit can be found in the La Porte County Historical Society Museum today. In addition, Belle Gunness has inspired musical songs, a 2004 film, Method, and an actual crime podcast, My Favorite Murder, which debuted in 2017.

There were several movies and publications based on Gunness and her mass murders.

Camilla Bruce’s 2021 novels The Black Widow of LaPorte, The Mistress of Murder Hill: The Serial Killings of Belle Gunness, America’s Femme Fatale: The Story of Serial Killer Belle Gunness, The Mystery of Belle Gunness, Butcher of Men, The Mistress of Murder Hill: The Serial Killings of Belle Gunness, with elements of Norwegian noir and true crime, Hell’s Princess: are some notable publications.

The Belle Gunness farm became a tourist attraction once Gunness’ crimes were revealed.

Visitors from all around the country came to visit the mass graves, and concessions and souvenirs were offered. Furthermore, the crime became a part of local history, with a permanent “Belle Gunness” exhibit at the La Porte County Historical Society Museum.

References

https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-belle-gunness-murder-farm