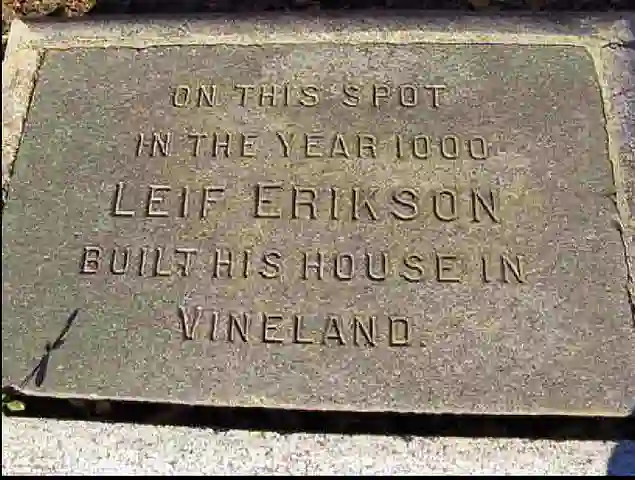

Vikings explored the area of coastal North America known as Vinland or Winland. As the remnants of timber houses at L’Anse aux Meadows on Canada’s northern edge of Newfoundland attest, Leif Erikson landed there approximately 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the journeys of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot.

Vinland is well-known for its wild grape cultivation.

The word appears in the Vinland Sagas and refers to Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence as far north as northeastern New Brunswick. Much of the sagas’ geographical information corresponds to modern knowledge of transatlantic travel and North America.

So where is Vinland? What happened to it? Many people claim to have discovered it from northern Labrador to Virginia. is it the genuine Vinland? As do old Icelandic texts, Leif left only a few tantalizing clues.

To solve the enigma of Vinland, these must be combined with archaeological finds, an understanding of what the Vikings were capable of, their motivations, and an understanding of the people and environment of the land they encountered.

What is Vinland, and Why is it So Special?

Vinland, sometimes known as the “Land of Wine,” is not depicted on any modern map. However, 1000 years ago, it was the setting for a watershed moment in world history. The Vikings were the first Europeans to set foot on the so-called “New World,” according to Icelandic sagas, 500 years before Columbus sailed a ship. They even built a short-lived town.

The principal sources of information regarding the Norse travel to Vinland are two Icelandic Sagas known as the Vinland Sagas: the Saga of Erik the Red and the Saga of the Greenlanders. Oral tradition kept these stories until they were written down approximately 250 years after the described events.

Because they share many tale elements but employ them in different ways, the existence of two versions of the story demonstrates some of the limitations of using traditional sources for history. One probable example is the mention of two separate men named Bjarni, both of whom are blown off course.

According to the sagas, there were a large number of Vikings in the parties that visited Vinland. Thorfinn Karlsefni’s crew numbered 140 or 160 persons according to Erik the Red’s Saga and 60 according to the Greenlanders’ Saga. According to the latter, Leif Ericson headed a crew of 35, Thorvald Eiriksson a 30, and Helgi and Finnbogi a 30.

As per the Saga of Erik the Red, orfinnr “Karlsefni” órarson and a company of 160 men traveled south from Greenland and discovered Helluland, another stretch of sea, Markland, another period in the sea, the headland of Kjalarnes, the Wonderstrands, Straumfjör, and finally Hóp.

In this bountiful place, no snow falls during winter. However, after spending several years away from Greenland, they decided to return when they recognized that they would otherwise face an eternal war with the indigenous.

The Vinland colonists were aware of, and took back with them, the existence of land beyond Greenland. But they only knew about Newfoundland and possibly parts of the Canadian coast. It appears that they were unaware of the size of the territory beyond that point.

That was all Leif Erikson, and his people knew. Beyond Greenland, some unfriendly native land did not lend itself to a large colony. They didn’t seem to realize it wasn’t simply “someplace” or that it was more than just the next Greenland, which wasn’t particularly unique in and of itself.

If you follow the sagas as if they were a tour guide, directly turning their places into bright dots on detailed maps is not a simple question of tracing the actual historical presence of the Norse in North America.

Much debate has centered on determining which locations the Vikings may have visited in the decades preceding 1000 CE to reconcile the scant archaeological evidence with speculations based on saga accounts.

Vinland, the Norse name for the land they discovered, reflected reality. Archaeological finds at L’Anse aux Meadows demonstrated that the Norse did travel south to locations where wild grapes thrived. The wine was a luxury drink loved by the elite of Norse culture as part of a flashy lifestyle, and it was used to gain power and influence.

The area with grapes closest to L’Anse aux Meadows is eastern New Brunswick. Therefore the Norse made their discovery there. It was also a region with spectacular hardwood trees from which great timber could be extracted, a valuable resource for Greenlanders who lacked forests.

Why did the Vikings Abandon Vinland?

Vinland was a long way from even Greenland, which was small and sparsely populated. Iceland was the nearest major trading port, but it was a long way away. Resupply and trading were particularly difficult in the North Atlantic, which is notoriously turbulent.

The existence of aboriginal peoples was another reason that hindered the Norse from establishing a permanent colony in Vinland. Eastern New Brunswick was home to the Mi’kmaq, a vast and densely populated people who could provide significant resistance to Viking incursions.

Discovery of the Vinland

Archaeological evidence of the sole known Norse settlement in North America was discovered in 1960. It is made up of eight timber-frame structures with thick sod walls, similar to those seen in Greenland and Iceland. Some were homes, while others were forges and workplaces.

The excavations turned up traces of iron manufacture and ship maintenance, among other things. According to experts, this cluster of dwellings and workshops could have housed 70 to 90 people year round and took at least two months to build.

L’Anse aux Meadows was discovered on the island of Newfoundland’s northern tip. Vinland was solely known via sagas and medieval historiography before the finding of archaeological evidence. The 1960 discovery bolstered the pre-Columbian Norse exploration of North America’s landmass.

Conclusion

Greenland’s limited population and the scale of the Vinland project have already been addressed, as have the tremendous distances involved. Add to that the northern Atlantic’s short sailing season and maintaining regular commercial traffic would have been a significant burden, if not outright impossible.

The presence of thousands of indigenous going about their business on the land would have made North America’s riches much more challenging to reach. Overall, despite the rich resources Vinland and its neighboring regions provided for the traveling Norsemen, the Vinland expedition was probably too much of a headache to be worthwhile.

On the other hand, Europe was closer, had many more personal and political connections, and shared enough resources that commerce there would almost certainly have taken precedence over Vinland excursions. And slowly but surely, Vinland became a lost city.