Beale Ciphers the Long-Lost Treasure of the United States

The Beale ciphers are a set of ciphertexts (3 ciphers) that supposedly discloses the location of a buried treasure of gold and silver valued at more than $80 million. The first (unsolved) text specifies the site, the second (solved) text accounts for the treasure’s content, and the third (unsolved) text provides the names of the treasure’s owners.

The three ciphertexts’ plot is based on an 1885 publication called The Beale Papers, which details a treasure hidden by a person named Thomas J. Beale in a hidden place in Bedford County, Virginia, around 1820. Beale left after entrusting a box carrying the encrypted communications to a local innkeeper named Robert Morriss.

Nobody has been able to crack the first or third ciphers in over a century of effort.

History Behind Beale Ciphers

During the early 1800s, Thomas J. Beale discovered an abandoned mine containing gold, silver, and gems in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Beale and 30 other explorers moved the things to Bedford County, Virginia, where they were buried.

He then devised three ciphers (encoded letters) describing the treasure, its location, and the contact information of those who assisted him in burying it.

Beale placed the letters in an iron box and gave it to a friend, directing him to open it only if he hadn’t returned in ten years.

That was a significant understatement. Beale explained in a letter that he and his companions had traveled west to New Mexico in the late 1810s on a hunting excursion and discovered a gold mine there.

The guys gave up their enjoyment of working the mine, making a fortune in gold — “as well as silver, which had also been discovered,” according to the letter. The gang wasn’t sure what to do with their unexpected wealth. Still, they eventually handed it to Beale, who traveled back east and buried it in a cave near a Bedford County pub “which all of us had visited, and which was regarded a very safe depository,” according to the letter.

Beale and his companions later returned and relocated the treasure to a new place. The gang also urged Beale to give details on how to find the treasure to some “absolutely reliable person” so that if they perished during their adventures, their families might be compensated.

A treasure that huge would have required numerous wagons to transport it. It would have had to pass an international border before being transported over the Mississippi River and across many states.

It would then have to be transported over the Appalachian Mountains and buried. That kind of project would have required hundreds of people, and keeping it a secret would have been difficult.

According to the account, the innkeeper opened the box 23 years later and shared the three encrypted ciphertexts with a friend before dying decades later.

The friend of Morriss then spent the next twenty years of his life attempting to decipher the signals but was only able to solve one of them, which revealed the buried treasure’s details and the prize’s overall location. The unidentified acquaintance then released all three ciphertexts in a pamphlet for sale in the 1880s.

Thomas J. Beale’s Appearance

The Inn owner Rober Morriss described Beale as follows.

“In person, he was nearly six feet tall, with jet black eyes and hair of the same color, worn longer than was the vogue at the time,” Robert Morriss recalled.

His form was symmetrical and demonstrated unusual strength and activity; however, his distinguishing feature was a dark and swarthy complexion, as if extensive sun and weather exposure had thoroughly tanned and discolored him.

This, however, did not detract from his look, and I thought him the noblest man I had ever seen.”

Beale Ciphers Encryption Method

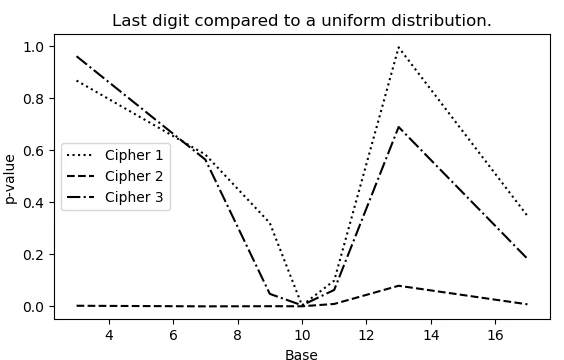

The encryption method used for the second Beale cipher results in a -Benford’s distribution for the first significant digit of the coded message’s numbers. The second decoded cipher has a relative level of divergence from Benford’s law of roughly ε 0.15.

The other two undeciphered codes deviate from 0.15-Benford’s law statistically significantly, implying that either ciphers 1 and 3 are fake or that the encryption method used to encode them differs from that used for cipher 2.

Attempts in Discovering the Treasure

Morriss eagerly went about cracking the three ciphers. But, despite years of effort, he was no closer to breaking the ciphers. Before his death, the innkeeper delivered the three encrypted ciphers to a friend to assure their safety. Morriss’ friend’s identity remains unclear.

That companion spent the next two decades deciphering the ciphers hoping to discover the massive, buried treasure. After twenty years of real hard work, he solved only one of the three messages.

The only cipher broken was the second, which described the contents of the treasure trove. As a book cipher, Beale utilized a modified version of the Declaration of Independence. The last two ciphers remain a mystery to this day. It detailed the location of the hidden treasure.

The Hart brothers, George and Clayton, were among the most passionate treasure searchers drawn to the Beale ciphers. They sifted through the files for decades, but Clayton Hart gave up in 1912, and George lost hope in 1952. Hiram Herbert, Jr., who first discovered Beale, has been an even more ardent supporter.

who began fascinated in 1923 and maintained his fixation until the 1970s He, too, was left with little to show for his efforts.

Professional cryptanalysts have also joined the hunt for the Beale treasure. The Beale ciphers piqued the interest of Herbert O. Yardley, who formed the United States Cipher Bureau at the end of World War 1, and Colonel William Friedman, the prominent player in American codebreaking throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

While in charge of the Signal Intelligence Service, he included the Beale ciphers in the training curriculum because he thought they were of “diabolical genius, deliberately designed to mislead the unwary reader.” Military historians commonly use the Friedman archive, which was established at the George C. Marshall Research Centre after his death in 1969.

Many visitors are die-hard Beale fans. Carl Hammer, retiring director of computer science at Sperry Univac and a pioneer of automated codebreaking, has recently emerged as a critical figure.

Several excavations near the summit of Porter’s Mountain were conducted, one in the late 1980s, with the landowner’s approval if any treasure found was split 50/50.

The treasure hunters, however, only discovered Civil War artifacts. The expedition broke even since the value of these items covered the costs of time and equipment rental.

At least 10% of the country’s greatest cryptanalytic minds. And not a single penny of this work should be resented. The work, including the routes that led down blind alleys, has more than paid itself for expanding and refining computer research.”

Conclusion

Numerous people who have firmly felt that the Beale Treasure narrative contains a significant amount of truth and authenticity handle the matter largely in two ways.

They either go on a physical discovery of the fortune after exploring and evaluating with as much as can be fairly expected given what is provided, or they don’t. Or they devote their efforts to untangling the codes. Many people have physically searched for the treasure over the years with little success.

The search for these missing jewels will continue until further confirmation and evidence can be produced to either prove or reject the highly mythical Beale Treasure. The beauty, fame, and popularity gained by the individual who completes this enormously difficult feat and obtains fortune are enough to keep people interested.