What Happened to Marilyn Sheppard? The Unsolved Mystery

Marilyn Sheppard, the wife of a thirty-year-old doctor named Sam Sheppard, was murdered in the bedroom of their house in Bay Village, Ohio, on the shores of Lake Erie, on July 4, 1954. Sam Sheppard denied any role in the murder and described his confrontation with the killer.

Did Sam, do it? It’s unusual for a murder mystery to go unresolved for over 50 years. If the riddle is not entirely answered during the trial, subsequent admissions of previously discovered clues or more sophisticated forensic tests almost always reveal what the prosecution did not.

But not so in the case of Sam Sheppard. Sam Sheppard was judged guilty by one jury and not guilty by the other, twelve years apart.

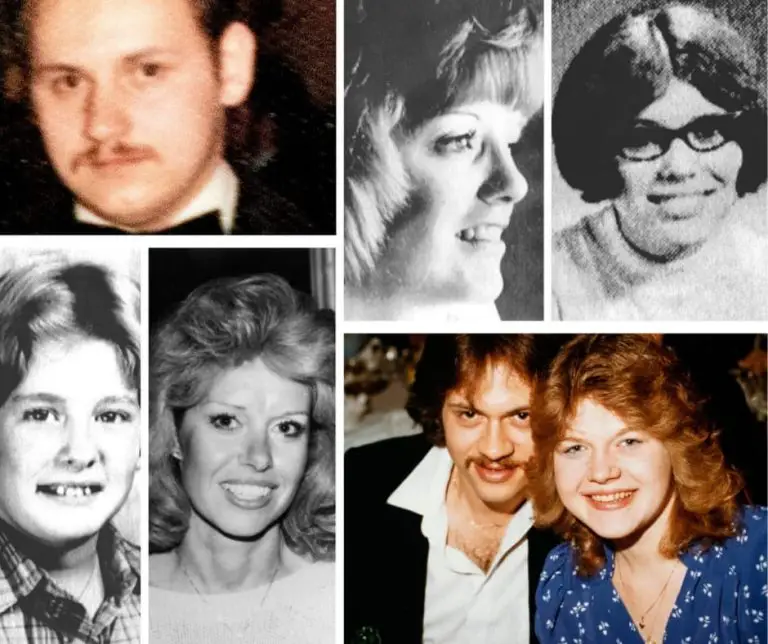

The Family of Marilyn and Sam Sheppard

In the summer of 1954, Sheppard’s had been married for nine years, and the couple had a seven-year-old son and a second child on the way. They lived in a house on the edge of Lake Erie in Bay Village, Ohio, a Cleveland suburb.

Both Marilyn and Sam Sheppard were prominent local family and active community members.

The Series of Events happened on That Fateful Day

Sam and Marilyn Sheppard hosted neighbors at their lakefront home on Saturday, July 3, 1954. Sheppard fell asleep on the living room daybed as they were watching Strange Holiday. Marilyn led the neighbors away.

Marilyn Sheppard was hacked to death in her bed with an unknown device in the early morning hours of July 4, 1954. The bedroom was coated in blood spatter, and there were blood drips on the flooring throughout the house. Some things from home looked to have been stolen, including Sam Sheppard’s wristwatch, keychain and key, and fraternity ring.

They were eventually discovered in a canvas bag in the undergrowth behind the home. Sam claims he was sleeping soundly on a daybed when he heard his wife’s cries. Before being knocked unconscious, he ran upstairs and spotted the intruder in the bedroom.

When he awoke, he noticed the intruder downstairs and raced him down to the beach, where they fought, and Sheppard was knocked unconscious again.

Spencer Houk, the mayor of Bay Village, received a phone call from Sheppard shortly before 6:00 a.m. on July 4. He was urging Houk to come over to his place. Soon later, Mayor Houk and his wife Esther arrived at Sheppard’s house, finding him shirtless and dressed in dripping wet jeans; his face was battered and swollen.

Esther entered her bedroom upstairs. The contents of Sheppard’s medical bag were thrown across the floor, and his desk drawers had been taken. Esther discovered bloodstains on the floor, walls, and bedspread.

Marilyn Sheppard’s body lay on her bed, surrounded by pools of blood. Her pajama top was wrapped up over her neck, and she had cuts on her face. According to the coroner, Marilyn had 35 distinct wounds, most of which were on her face and head. She’d been beaten to death.

Mayor Houk called the police and Sheppard’s brother Richard after arriving at Sheppard’s house. When Richard arrived, he briefly checked Marilyn’s body to see if they could save her, but he managed only to confirm that she was dead. After that, Cleveland police, the coroner, and Sheppard’s other brother, Steve, arrived on the scene.

The two brothers assessed Sheppard’s injuries and took him to the family’s neighboring clinic for neck treatment. Newspapers later said that the brothers whisked Sheppard away to avoid questioning, but the police officers on the scene made no objections when he left, and they were able to question Sheppard three times later that day.

The Trail of Sam Sheppard

Sheppard’s trial was scheduled to commence on October 18, with Sheppard maintaining his claim of confronting and fighting the perpetrator. Extensive pre-trial publicity around the country made the case so well-known that it created a frenzy when the trial date arrived.

The national media gathered outside the courthouse, on the sidewalks and stairs, to photograph Sheppard and the other trial participants.

The judge reserved space in the courtroom for television and press reporters. Radio broadcasting equipment was built up at the courthouse so that daily newscasts could be made throughout the trial.

Newspapers ran word-for-word accounts of the day’s proceedings in court, along with images of the participants and exhibits introduced at trial. The new medium of television provided unprecedented media exposure in American history.

The jury visited the murder scene on the first day of the trial. One news media member was allowed to accompany the jury as they inspected the Sheppard residence.

Outside, hundreds more reporters, camera operators, and passersby waited. The case was assigned to the jury for deliberation on December 17.

Four days later, they returned with a guilty verdict. Sheppard was found guilty of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison. On the night of the judgment, the Cleveland Press sold 35,000 extra copies of their newspaper.

No clear evidence was found that explicitly linked Dr. Sam Sheppard to his wife, Marilyn, death. Despite this, on July 30, 1954, Bay Village police arrested Sheppard on a murder accusation.

The subsequent murder trial resulted in a guilty verdict. The doctor, formerly respected and admired, was suddenly dubbed a killer.

Throughout his trial and after his conviction, Sam maintained his innocence. Dr. Sam Sheppard was imprisoned for ten years until the state of Ohio granted his appeal and granted him a new trial.

On June 6, 1966, the murder conviction was reversed due to a lack of evidence. Dr. Sam Sheppard was a free man from that moment until he died of liver disease on April 6, 1970.

Criticism of the Trial and the First Verdict

When police arrested Sheppard under a torrent of criticism from the media, and all of the jurors for the case were being chosen, the names of the sixty-four jurors from whom the court had to choose were published in the newspaper, along with their residences and phone numbers.

This elevated them to the status of celebrities, allowing members of the media and those who had nothing to do with the case to approach them and voice their opinions.

As if the press wasn’t already having a field day with this case, Judge Blythin permitted his courtroom to be packed with reporters from national and local news organizations. He even sealed off another area for radio reporters to do their stories.

The never-ending swirl of media attention became even worse as the trial progressed and the case against Sheppard began. During the trial, New York gossip columnist Walter Winchell reported that a woman had come forward and admitted to having a child with Sam Sheppard.

The jurors were never truly isolated or barred from using the phone or reading the newspaper during the trial, so they were also subjected to all the media propaganda.

The witnesses were also subjected to media influence since, while they were not permitted to enter the courtroom during the trial, they were allowed to read verbatim transcripts of the proceedings in the newspaper.

One newspaper featured a quotation from the judge himself declaring Sheppard was guilty, in one of the clearest examples of how the media could infiltrate the population’s minds.

With all of the media attention surrounding the case and the relentless bombardment of negative media directed at Dr. Sheppard, it only took the jury four days to deliberate on the evidence and reach a judgment finding Sam Sheppard guilty of second-degree murder. It only took a few minutes after hearing the guilty verdict for Judge Blythin to sentence Sam Sheppard to life in prison.

Theories Regarding Marilyn Sheppard’s murder

Over the years, three critical possibilities for identifying the killer have emerged. Sam Sheppard’s story of the killing for which he was convicted fell apart during a retrial, and he was acquitted. Sam was a broke alcoholic at the time of his death, yet he insisted that a bushy-haired burglar murdered his wife.

Another suspect was Richard Eberling, a window washer who was in the house the day before the crime. Later, Richard was convicted of killing an elderly widow, although he maintained until he died in prison that he had no involvement in Marilyn’s death. In his original testimony to police, Sam Sheppard claimed a confrontation with two people.

Next-door neighbors Bay Village Mayor Spencer Houk and his wife fit this description and had a motivation. This was brought to the grand jury, but no charges were filed. The couple has now died.

Sam Sheppard’s Later Life

Sheppard briefly returned to his medical practice after his release from prison and later worked briefly as a pro wrestler under the alias “The Killer Sheppard.”

Sam Sheppard, who became a strong drinker in his latter years, died of liver failure on April 6, 1970, at 46. His son has made numerous attempts to clear Sheppard’s record, including unsuccessfully suing the government in 2000 for his father’s unlawful imprisonment.

More Recent Developments in this Case

Sheppard’s body was buried until September 1997, when it was excavated for DNA testing as part of his son’s case to clear his father’s name. DNA results cleared Sheppard of the murder. Following the tests, the body was burned, and his ashes were placed alongside those of his deceased wife, Marilyn, in a mausoleum at Knollwood Cemetery in Mayfield Heights, Ohio.

Alan Davis, Sheppard’s lifelong friend and executor of his estate, sued the State of Ohio in 1999 for Sheppard’s unlawful imprisonment.

The case went to an eight-person civil jury after ten weeks of trial, 76 witnesses, and hundreds of documents. On April 12, 2000, the jury debated for only three hours before returning a unanimous finding that Samuel Reese Sheppard had failed to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that his father had been wrongfully imprisoned.

The Eighth District Court of Appeals found unanimously on February 22, 2002, that the civil lawsuit should not have gone to a jury since the statute of limitations had elapsed, and a claim for wrongful incarceration had expired with Sam Sheppard’s death. The Supreme Court of Ohio rejected to review the appeals court’s ruling in August 2002.

Conclusion

So, who assassinated Marilyn Sheppard? If Sam Sheppard is not guilty. Did he hire someone to attack on his behalf if he didn’t do it himself? These questions have been unanswered for more than five decades.

The unique and legendary murder case had such an impact on American society that it is commonly assumed to have inspired the popular 1960s television series and 1993 film, The Fugitive.

The innocent doctor is suspected of murdering his wife in the television version and a later film version, but he escapes from prison and spends years on the run-in search of the actual killer.

Both the fictitious and real-life stories ended with the husband’s acquittal. Although the killer is arrested in the film version, the killer was never apprehended in the real-life Sheppard case.

References

https://edition.cnn.com/2000/US/02/23/sheppard.trial/

https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1014&context=uhf_2009